Critical Care for Turtles

Module Goals

- Know where and how to give injections and perform venipuncture.

- Understand how to administer fluid therapy in turtles.

- Be able to describe common drugs for analgesia in turtles and compare to what you have in your clinic.

- Know how to perform tube feeding and administer oral medications

- Be able to assess viral turtles and give eye drops

If you would like to listen to an audio recording of this material, please click here. (Duration: 16:38)

Injections

As chelonians have a slow metabolism and oral administration of drugs can pose a challenge, most medications are given via injection. It is recommended to only inject medications into the cranial half of a turtle’s body (unless dangerous in species such as snapping turtles) due to the renal portal system and its possible first-pass effect on drug absorption.

Intramuscular Injections

Intramuscular (IM) injections are given in the brachial or pectoral muscles. Insert the needle at a 45-90 degree angle directly in between scales on the forearm and aspirate to ensure you get negative pressure before injecting. The tail of snapping turtles can be used for intramuscular injections.

Subcutaneous Injections

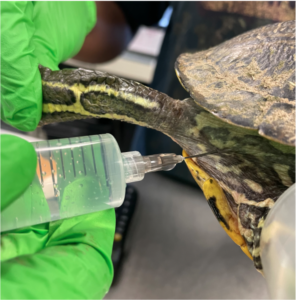

Subcutaneous (SQ) injections are given under the loose skin proximal to the forearms in the space next to the neck. Insert the needle and aspirate before injecting. This is also where subcutaneous fluids are given.

Intravenous Injections

Intravenous (IV) injections are more challenging to administer due to the small size and lack of visualization of reptile vessels. Typically IV injections include anesthetics, some analgesics, and euthanasia solutions.

Insert the needle on midline into the skin dorsal to the neck at the junction of the skin and carapace. Direct the needle dorsally while creating a vacuum with the needle until blood is aspirated, then inject.

Recommended for snapping turtles where the cranial locations are inaccessible. Insert the needle at a 45- 90 degree angle in between the scales on the dorsal midline of the tail. Direct towards the coccygeal vertebrae and once hit, aspirate with the needle and continue to hold suction while slowly backing the needle out until blood is aspirated, then inject.

Only recommended for euthanasias due to pain and proximity to the spinal cord. Insert the needle in the dorsal midline skin of the neck, with a 90 degree angle, just caudal to the occipital process. In freshwater turtles, flex the neck to insert the needle caudal and ventral to their longer occipital process, and direct towards the tip of the nose. Pull back on the syringe and inject once blood is aspirated.

Venipuncture

Collecting blood in chelonians is a good skill to have for acquiring diagnostics such as PCV/TS, lactate, and blood glucose. A blood smear may also be beneficial when making treatment decisions.It is important to keep in mind that the lymphatic system may contaminate your blood collection due to the proximity of lymphatic vessels to the blood vessels – turtles lack lymph nodes. It may also be beneficial to heparinize the syringe to avoid clotting due to the slow bleeding seen in many chelonians, however, there are risks including sample dilution and possible injection into the turtle so we recommend expelling as much heparin as possible. It is important to not use collection tubes containing EDTA as it lyses reptile erythrocytes.

Common sites for chelonian venipuncture are described below:

| Description | Visual | |

| Subcarapacial sinus | Insert the needle on midline into the skin dorsal to the neck at the junction of the skin and carapace. Direct the needle dorsally while creating a vacuum with the needle until blood is aspirated. Note that if using this site to draw blood for diagnostics, you can expect marked lymph contamination due to the proximity to lymphatics. You may need to redirect your needle if you are drawing lymph or serosanguineous fluid. |

Site of subcarapacial IV injection or venipuncture |

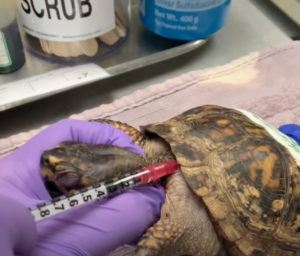

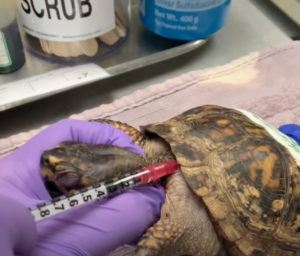

| Jugular vein | Extend the neck of the turtle and insert your needle superficially parallel to the dorsal edge of the tympanic membrane. In some species, palpation or visualization of the jugular vein may be possible but in others, it may be hard to find. Recommended due to lack of lymph contamination. |

Site of jugular vein for venipuncture. |

| Brachial vein | Extend the forearm and insert your needle into the groove in between the elbow joint and the prominent tendon. Advance the needle as far in as the joint and apply a vacuum while slowly withdrawing until you get a flash of blood. |

Site of brachial vein venipuncture. |

| Femoral vein | Can be done with the turtle in dorsal or sternal recumbency. Extend the hind limb and insert your needle into the groove between the knee joint and the prominent tendon. Advance the needle as far in as the joint and apply a vacuum while slowly withdrawing until you get a flash of blood. |

Site of femoral vein venipuncture. |

| Dorsal coccygeal vein | Recommended for snapping turtles where the cranial locations are inaccessible. Insert the needle at a 45- 90 degree angle in between the scales on the dorsal midline of the tail. Direct towards the coccygeal vertebrae and once hit, aspirate with the needle and continue to hold suction while slowly backing the needle out until blood is aspirated. |

Site of dorsal coccygeal IV injection or venipuncture. |

Table 1. Venipuncture sites in chelonians.

Fluid Therapy in Turtles

Assess hydration by checking for sunken eyes, tenting of skin, dry mucous membranes, or thick ropey oral mucous. The most common types of dehydration in turtles are isotonic dehydration which generally occurs as a result of hemorrhage and short-term anorexia, or hypotonic dehydration which happens after prolonged anorexia. To treat these we typically use Lactated Ringers Solution (LRS).In chelonians, rehydration fluid therapy is generally 2-3% of body weight or 20-30 ml/kg/day for maintenance. This can be established based on the degree of dehydration while keeping in mind that anemia or hypoproteinemia due to over-hydration is a possibility. Also, consider fluid therapy in dry docked or post-anesthetic turtles. Administration of fluid therapy in TRT is typically given subcutaneously in the inguinal area or in loose skin in front of front limbs. Do not give subcutaneous fluids for more than 2 weeks. This can lead to subcutaneous inflammation and abscesses – we recommend an esophageal feeding tube for patients which must be dry-docked for more than 2 weeks so that fluids can be offered that way.

Analgesia

Analgesia is a key component of managing critical chelonian cases, as morbidity and mortality have been shown to increase without proper pain management. Some turtles with severe pain may become lethargic or even depressed, and sometimes they will close their eyes. Other turtles will show no signs of pain at all, or pain can be hidden by the stress of hospitalization. Anorexia can be a sign of pain in turtles, but they will often refuse to eat in captivity whether they are in pain or not, so this is not a consistent indicator of pain. We discuss the analgesics we commonly use in the Turtle Rescue Team in the “Anesthesia and Analgesia” module. As most small animal clinics do not carry these drugs, there are also other options described in Carpenter’s exotic animal formulary and other literature that we have included here. It is important to remember there is a lack of knowledge regarding analgesia in reptiles especially involving the efficacy between different species. NSAIDs:

| Meloxicam | 0.2-0.5 mg/kg IM or PO q 48 hours

(IM administration is more efficacious) |

Opioids:

| Buprenorphine | 0.075-0.1 mg/kg SQ/IM q24 hours |

| Morphine | 1.5 mg/kg SQ/IM/IV q24 hours |

| Hydromorphone | 0.5-1.0 mg/kg SQ/IM q24 hours |

| Methadone | 3-5 mg/kg SQ/IM q24 hours |

| Tramadol | 5-10 mg/kg PO q48-72 hours |

| *Butorphanol can be given for sedation but has no shown analgesic efficacy alone | 0.2 mg/kg IM |

Local Anesthetics

| Lidocaine 1% or 2% | 1-2 mg/kg SQ |

| Bupivacaine 0.5% | 1 mg/kg SQ |

Other Anesthetics

| Medetomidine/Dexmedetomidine | 0.05-0.3 mg/kg SQ, IM |

| Ketamine | 5-10 mg/kg IM |

| Midazolam | 1-2 mg/kg SQ, IM |

| Propofol | 3-10 mg/kg IV |

Administering Oral Medications and Tube Feeding

Oral medications are indicated in turtles based on drug availability, labeled use of certain drugs, and most commonly when giving cod liver oil to supplement vitamin A. As hypervitaminosis A can be iatrogenically induced when giving injectable vitamin A, oral cod liver oil can be a safer alternative.

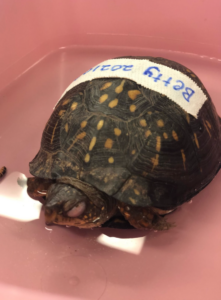

Turtles with hypovitaminosis A frequently present with swollen eyes, a nasal discharge, tympanic (aural) abscesses, and in advanced cases, respiratory distress. There is some evidence that environmental organochlorine toxicity inhibits vitamin A metabolism in wild box turtles and contributes to aural abscesses and upper respiratory disease.

Oral medication can be dabbed onto food or injected into an enticing treat (ex. mealworm) if the turtle has a good appetite. It can also be administered via syringe or feeding cannula, however, this can prove difficult in turtles when they retract their head and obscure their oral cavity.

Tube Feeding

Tube feeding may be indicated if a turtle has injuries that prevent it from eating on its own or it has been anorexic for an extended period of time and it needs nutrition to heal its injuries. While it is true that turtles may not eat for extended periods in the wild, these are usually in situations where the turtle is brumating and is not critically injured.

Tube feeding can be done up to every 48-72 hours, but we also will do it as rarely as once a month for turtles that are being rehabbed over the winter if they are not wanting to eat on their own. We use a commercially available reptile critical care formula, in which you mix powder with water or an electrolyte solution in a 1:3 ratio. It is labeled for use at 20-30 ml/kg per feeding, but often we will give only 10-20 ml/kg to avoid regurgitation. It is possible to tube feed foods such as crushed reptile pellets and water, dog food, and electrolyte solutions to aid in supplementing nutrition to injured reptiles, however, the Turtle Rescue Team does not employ these diets so we have no knowledge of effectiveness.

If the turtle will need to be tube-fed frequently or is hard to handle for feedings, an esophagostomy tube may be placed (see additional resources for procedure). This should be closely monitored and flushed with water after each feeding. It is also important to consider the risks of the sedation and a more invasive procedure when considering this option.

Tube feeding can also be done on a session-by-session basis via the oral cavity if the turtle is amicable to it. To do this an appropriately sized red rubber tube should be flushed with the liquid diet and inserted about ⅓ of the length down their shell to the level of their stomach. It is important to avoid the glottis located rostrally to the turtle’s esophagus. Once the tube is inserted all of the way into the turtle’s stomach, the liquid diet can slowly be given through the red rubber tube, while monitoring for any backflow or regurgitation. After the desired volume is administered, the tube can be flushed with water, kinked to avoid pulling the material up through the esophagus and removed. We then place the turtle with its caudal side down for about 10 minutes after feeding to help avoid regurgitation.

Assessing Viral Turtles

We see many turtles that have symptoms of infectious diseases, particularly viral diseases that can have a high mortality rate. The transmission of these viruses is unclear so we also want to prevent the spread of pathogens to other healthy animals as well as keep in mind environmental conditions that can increase morbidity, such as a low temperature. It is important to identify common viruses by their symptoms in order to isolate and treat the patient appropriately. We will occasionally identify viruses in our patients by PCR panels but will most often treat them symptomatically.

Herpesvirus

Chelonians are the most common reptile to be affected by herpesvirus and we suspect species such as Eastern Box Turtles often present to us symptomatic for this virus (terrapene HV1 and HV2). Symptoms can include lethargy, anorexia, rhinitis, conjunctivitis, stomatitis, glossitis, and subcutaneous edema. Eastern box turtles may also develop pneumonia, gastritis, enterocolitis, splenic vasculitis, hepatitis, interstitial nephritis. Oropharyngeal swabs, pharyngeal, and nasal mucosa samples may be submitted for PCR identification. As with other species, herpesvirus can remain as a latent infection with sea turtles being studied as lifelong carriers.

Ranavirus

Iridoviruses such as ranavirus have been an increasing concern in reptiles and can be transmitted by direct contact, contaminated water or soil, and possibly even mosquitos. It is also concerning as strains infecting turtles are not enveloped as with other strains making them resistant to organic disinfectants and stable in more environmental conditions. Symptoms include lethargy, anorexia, nasal discharge, conjunctivitis, severe subcutaneous cervical edema, and ulcerative stomatitis. Turtles can also develop hepatitis, enteritis, and pneumonia. Mortality has been shown to increase at lower temperatures, so as with other infections in ectotherms maintaining a proper temperature is important. Oral swabs, cloacal swabs, and blood can be submitted for PCR identification, as well as the yellow plaques that we will commonly see in the oropharynx.

Less common viruses affecting chelonians

Several other viruses that have been rarely reported in chelonians are listed with their symptoms below:

- Adenovirus- systemic disease, hepatic necrosis, and necrotizing enterocolitis.

- Reoviridae– stomatitis

- Paramyxoviridae- pneumonia, dermatitis

- Picornaviridae- softening of the carapace, stomatitis, rhinitis, conjunctivitis, ascites, tubular vacuolization in the kidneys

Treatment

Treatment for viral infections in turtles consists of supportive care including fluids, husbandry including proper temperature and humidity, supplemental feeding, and symptomatic care. Debilitated turtles are prone to upper respiratory disease and secondary bacterial infections such as mycoplasmosis so it is important to administer antimicrobials as necessary. An extremely common symptom in our turtles with upper respiratory disease is bilateral conjunctivitis, which we will treat with an ocular antibiotic (ciprofloxacin) and NSAID (diclofenac). To administer eye drops to turtles with extremely swollen eyes, a cotton-tipped applicator may be used to gently open the eye (multiple people may be needed to handle for treatment). Vitamin A injections or cod liver oral PO can be administered as well, as hypovitaminosis A is often associated with increased susceptibility to respiratory infections in turtles.

Relevant Videos

- Turtle Subcutaneous Fluids

- Turtle Venipuncture – Brachial Vein

- Turtle Venipuncture – Dorsal Coccygeal Vein

- Turtle Venipuncture – Jugular Vein

- Turtle Venipuncture – Subcarapacial Sinus

- Turtle Eye Drops

- Esophagostomy Tube Procedure

Additional Resources

- Divers SJ. Diagnostic techniques and sample collection. Chapter 43 in Divers S and Stahl S (eds.), Mader’s Reptile and Amphibian Medicine and Surgery, 3rd ed., Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2019. (PDF)

- Petritz OA and Son TT. Emergency and critical care. Chapter 87 in Divers S and Stahl S (eds.), Mader’s Reptile and Amphibian Medicine and Surgery, 3rd ed., Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2019. (PDF)

- Cutler D and Divers SJ. Esophagostomy tube placement. Chapter 45 in Divers S and Stahl S (eds.), Mader’s Reptile and Amphibian Medicine and Surgery, 3rd ed., Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2019. (PDF)

- Holmes SP and Divers SJ. Radiography – chelonians. Chapter 56 in Divers S and Stahl S (eds.), Mader’s Reptile and Amphibian Medicine and Surgery, 3rd ed., Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2019. (PDF)

- Sladky KK and Mans C. Analgesia. Chapter 50 in Divers S and Stahl S (eds.), Mader’s Reptile and Amphibian Medicine and Surgery, 3rd ed., Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2019. (PDF)

- Perry SM and Mitchell MA. Antibiotic therapy. Chapter 116 in Divers S and Stahl S (eds.), Mader’s Reptile and Amphibian Medicine and Surgery, 3rd ed., Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2019. (PDF)

Key Concepts

- Most medications are given to turtles by injections, including intramuscular, intravenous, and subcutaneous administration.

- Venipuncture in chelonians can be difficult and may be lymph-contaminated

- Fluid therapy is important for maintaing an adequate plane of hydration

- Oral medications and nutrition can be delivered via feeding needles or esophagostomy tubes.

- Turtles can contract a variety of viruses, most of which cause upper respiratory signs